Timeless Craft of Spanish Conservas

How Traditional Methods Preserve More Than Just Fish.

The morning air in Burela, a small coastal town in Spain's Galicia region, carries the distinct perfume of the sea as I watch a weathered boat dock with its precious cargo. José Vázquez, a third-generation fisherman whose hands bear the marks of decades pulling nets from these waters, carefully unloads gleaming silver-blue mackerel. But unlike most fish that race to market, these will undergo a transformation that connects centuries of tradition with contemporary cuisine.

"We fish at dawn because the fat content is perfect then," José explains, grabbing a fish to demonstrate. "Feel this," he insists, placing the mackerel in my palm. "The firmness, the oil in the skin—this is what makes conservas special. Not just any fish at any time will do."

José's catch is destined for Conservas Aréa, one of Spain's heritage producers where traditional methods of preserving seafood in tins have remained remarkably unchanged since the company's founding in 1883. Here, in facilities that would be recognizable to workers from a century ago, Spain's celebrated conservas tradition continues through practices that prize human touch over industrial efficiency, seasonal rhythms over constant production, and minimal intervention over technological shortcuts.

When Hands Tell the Story

Inside Conservas Aréa's processing room, I meet Carmen Rodríguez, who has been cleaning and filleting fish for over forty years. Her movements display a mesmerizing economy—no wasted motion, no hesitation. With a small, well-worn knife that she describes as "an extension of my fingers," she transforms whole fish into perfect fillets at a pace that seems impossible given her precision.

"Machine filleting damages the flesh," she explains without pausing her work. "It tears the delicate membranes, releases enzymes that affect flavor. The machines don't see the subtle differences between each fish—but my hands feel them."

Carmen is one of Spain's remaining maestras conserveras—female master canners whose specialized knowledge represents one of the country's oldest continuous professional traditions for women. These workers, often entering the trade as teenagers through family connections, develop tactile intelligence that machines cannot replicate.

At Conservas Güeyu Mar in Asturias, owner Abel Álvarez explains this irreplaceable human element: "The difference is judgment. A machine applies the same parameters to every fish. But Carmen and women like her make thousands of micro-decisions—this sardine needs ten more seconds on the grill; this anchovy requires slightly more pressure during cleaning; this tuna loin should be packed at precisely this angle to maintain texture during preservation."

This emphasis on handcraft differentiates traditional conservas from industrial canned fish. While standard commercial canneries process thousands of units hourly through automated lines, traditional producers measure daily production in hundreds, with each tin receiving individual attention.

"In industrial production, consistency means making everything identical," notes Pedro Martínez of Ramón Peña conservas. "In artisanal production, consistency means giving each piece exactly what it uniquely needs to achieve excellence."

The Dance of Seasons

On the wall of Conservas Ortiz's facility in the Basque Country hangs a calendar unlike any I've seen in modern production facilities. Rather than detailing production quotas or efficiency targets, it tracks natural cycles—the movement of fish, water temperatures, fat content patterns, and optimal harvest periods.

"We don't decide when to produce what," explains Carlos Ortiz, fifth-generation owner. "The sea decides, and we follow."

This seasonal attunement represents perhaps the most countercultural aspect of traditional conservas production in an era when global supply chains have largely eliminated seasonality from food systems. While supermarkets offer consistent products year-round, traditional conservas producers still operate according to natural rhythms that have governed fishing communities for centuries.

The calendar reveals distinct periods:

Spring brings tender young sardines and anchovies along Spain's Mediterranean coast, processed fresh when their delicate flavor is at its peak.

Summer marks the celebrated "Costera del Bonito"—the northern albacore tuna season—when facilities in the north work around the clock processing this prized catch during its brief availability from July through September.

Autumn brings robust mackerel and larger sardines with higher fat content, perfect for smoke-preservation techniques traditionally used in Asturias.

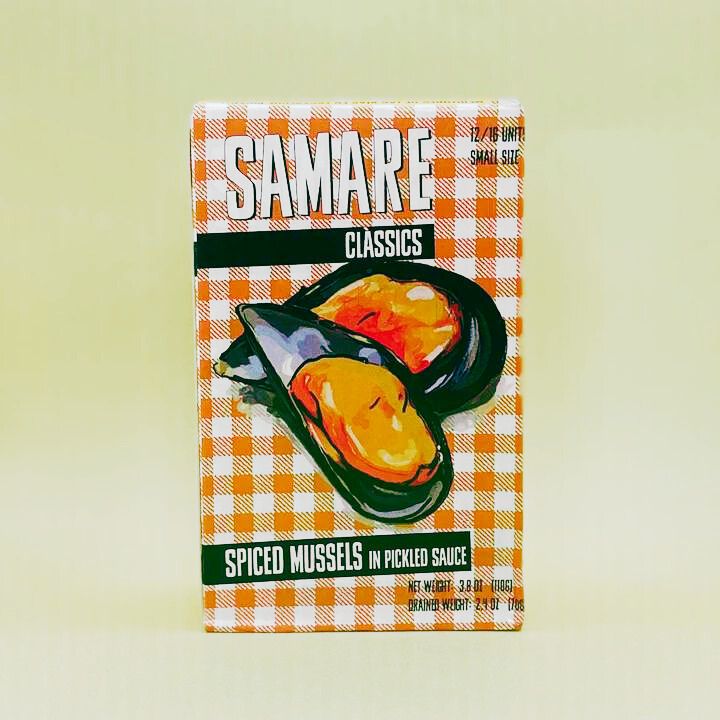

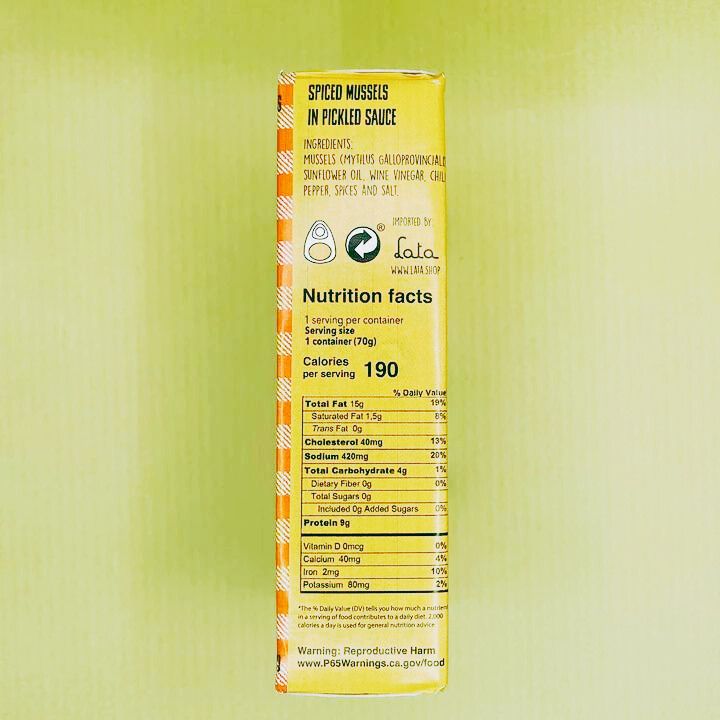

Winter sees focus shift to shellfish like cockles and mussels harvested from the rias (coastal inlets) of Galicia when water temperatures produce ideal texture and flavor.

This seasonal approach creates natural production breaks that allow for facility maintenance, worker rest, and sustained quality. During my visit to Conservas Los Peperetes in Galicia, workers were painting walls and refurbishing equipment during a seasonal pause—an impossibility in continuous production settings.

"Working with seasons rather than against them connects us to something larger than production schedules," reflects Antonio Pérez, the company's third-generation owner. "It reminds us we are participants in natural systems, not controllers of them."

This philosophy extends to purchasing decisions. While industrial canneries contract for specific volumes at predetermined prices, traditional producers often negotiate daily based on quality rather than quantity.

At the morning fish auction in Burela, I watch as buyers from premium conservas producers sometimes purchase just a fraction of a boat's catch—only those fish meeting exacting standards for size, fat content, and condition. The remaining catch goes to less exacting buyers.

"Some days we buy nothing," notes a buyer from Conservas Aréa. "Better to produce nothing than compromise quality. We can wait for the fish to be right."

The Alchemy of Minimal Intervention

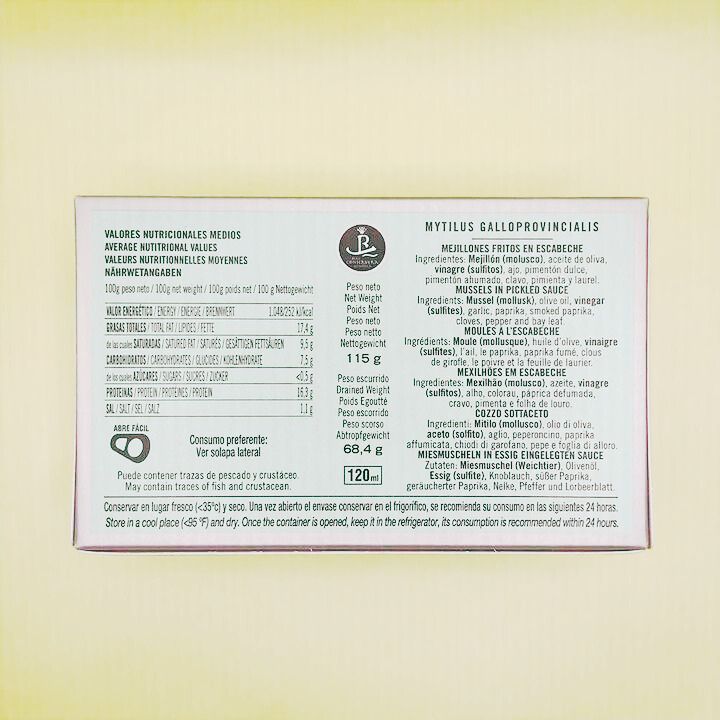

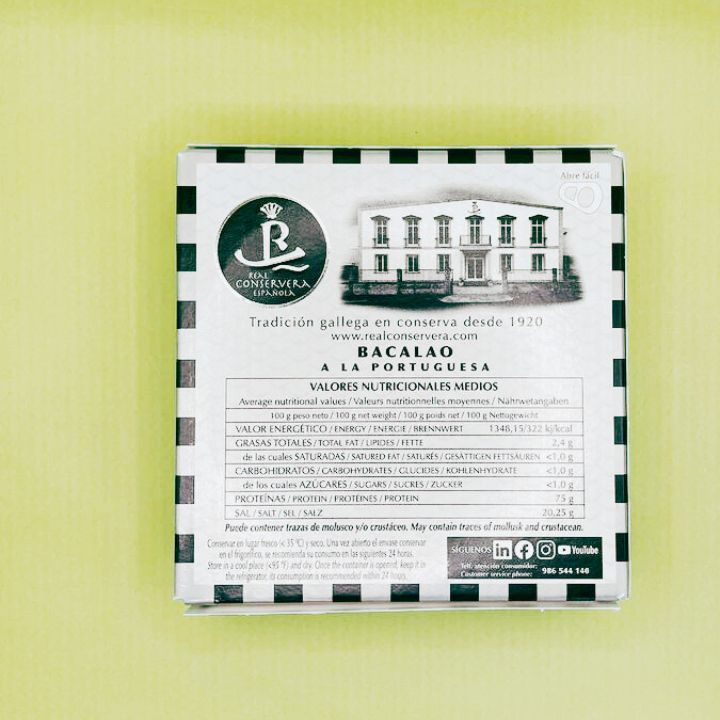

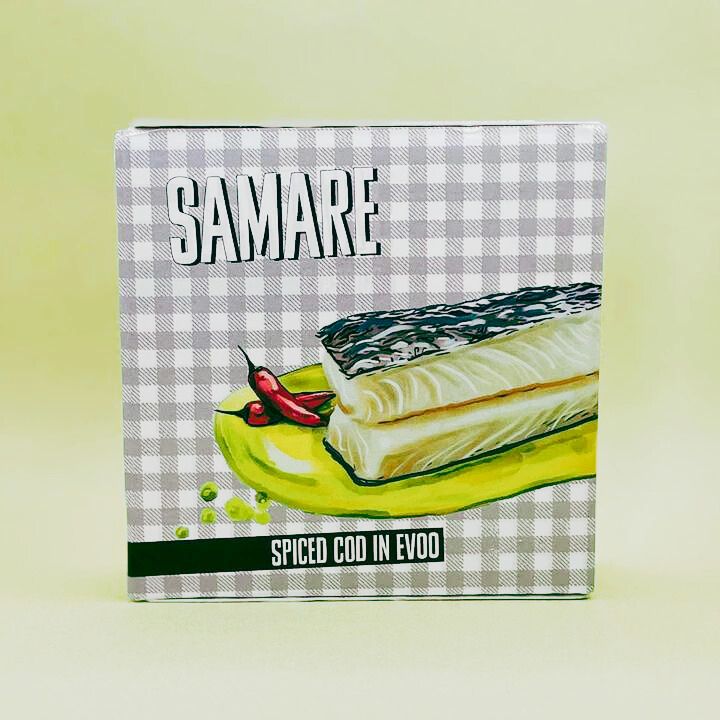

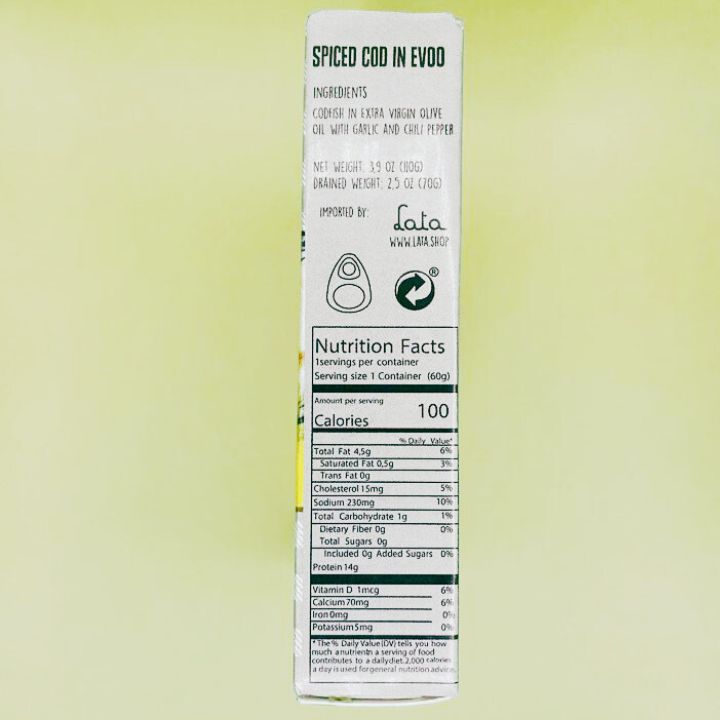

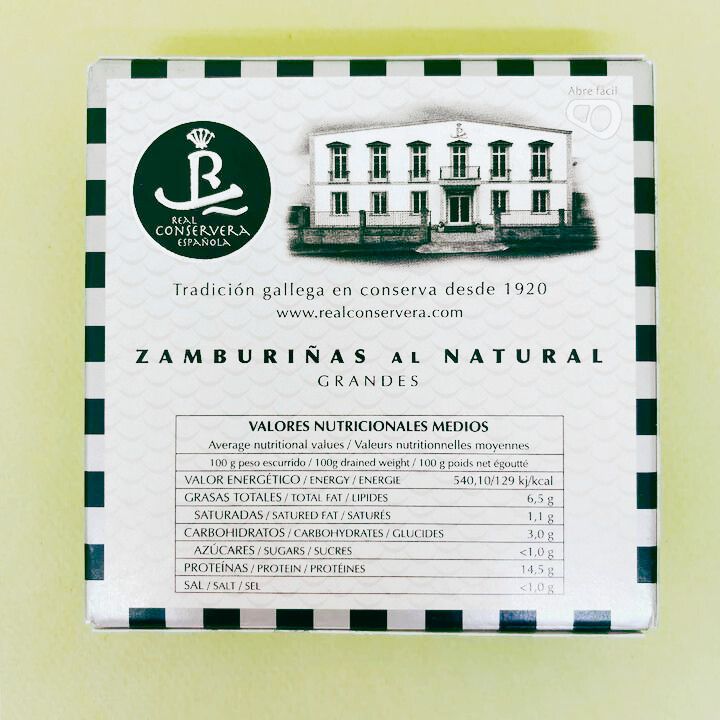

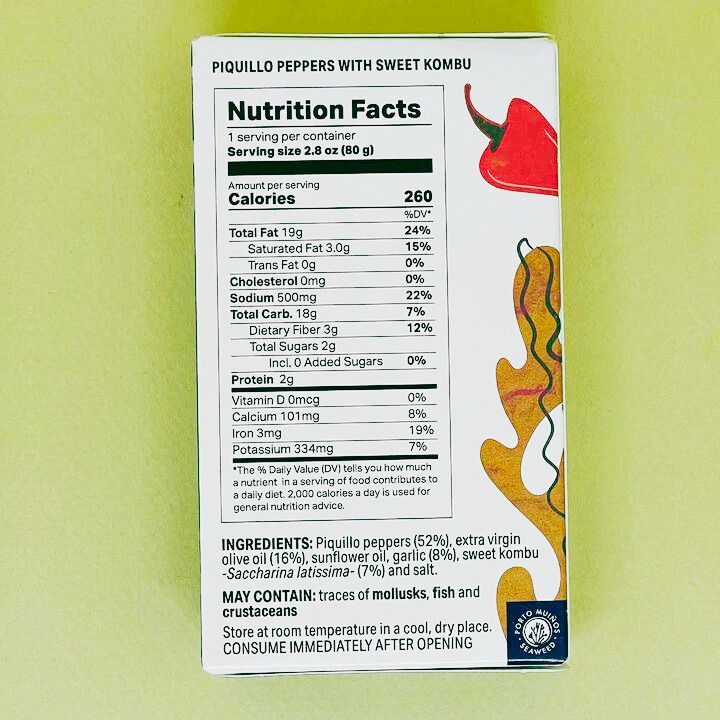

In an age of food technology promising ever-more complex formulations and processing techniques, traditional conservas production stands apart through its commitment to minimalism. The ingredients list on premium tins rarely exceeds three items: the seafood itself, olive oil, and perhaps a touch of salt.

"The fundamental principle is to preserve what the fish naturally offers rather than transform it into something else," explains María Jesús López, master blender at Conservas Brétema, as she demonstrates the traditional cooking process for sardines.

The fish, having been meticulously cleaned by hand, are briefly grilled over open flames—not to cook them fully but to seal the skin and set the proteins. They're then arranged in tins, spines removed with surgical precision by workers using specialized tweezers.

What happens next reveals the counterintuitive genius of traditional preservation: the addition of oil not as mere packing medium but as transformative element. María carefully measures extra virgin olive oil into each tin, explaining how the specific oil blend was selected to complement this particular catch.

"The oil is not just preventing oxidation—it's a cooking medium, a flavor carrier, and a textural element," she notes. "Each producer guards their oil blend recipes carefully. Some have remained unchanged for over a century."

The sealed tins are then slowly heated in steam chambers or autoclaves—a process that simultaneously sterilizes the contents and initiates a gentle cooking process that will continue long after the tins cool. Unlike industrial canning where high-temperature flash sterilization prioritizes speed over texture, traditional producers use longer, gentler heating curves that preserve delicate structures within the fish.

"We're not just stopping decay," María emphasizes. "We're creating conditions for something new to develop—like winemaking, where initial ingredients transform over time into something greater than their origins."

This transformative quality distinguishes fine conservas from merely preserved fish. Premium tins are dated not just for safety but for optimal consumption—many producers recommend waiting months or even years before opening certain varieties to allow flavors to develop and textures to achieve their ideal state.

At Conservas Ramón Peña, I'm shown the company's internal library of conservas dating back decades—tins kept not as historical curiosities but as reference standards for how products should develop over time. A 15-year-old tin of bonito is reverently opened, revealing fish that has undergone an almost alchemical transformation, with rich amber oil and flesh that separates into distinct pearl-like segments with the gentlest pressure.

"This isn't food preservation as mere technical achievement," remarks Pedro Martínez, watching my reaction to the aged bonito. "It's preservation as philosophical position—a belief that some things improve through patient waiting."

Masters of Fire and Steam

While much attention focuses on the hand-processing of fish, equal craftsmanship applies to the cooking techniques that prepare seafood for preservation. Traditional producers maintain distinctive approaches deeply rooted in regional cooking traditions.

In a small facility outside Bermeo in the Basque Country, I watch as workers tend wood-fired grills where sardines cook briefly before tinning. The oak wood imparts subtle smoke notes while high heat quickly seals the skin.

"We could use gas or electric—it would be much easier," admits the facility manager, wiping sweat from his brow in the intense heat. "But the flavor wouldn't be the same. The wood creates volatile compounds that become part of the fish."

This attention to cooking method varies by region and species. In Galicia, steam predominates for delicate shellfish like mussels and cockles, preserving their natural liquor that becomes part of the preservation medium. In Asturias, smoke plays a more prominent role, with some producers maintaining smoke chambers that have been in continuous operation for generations.

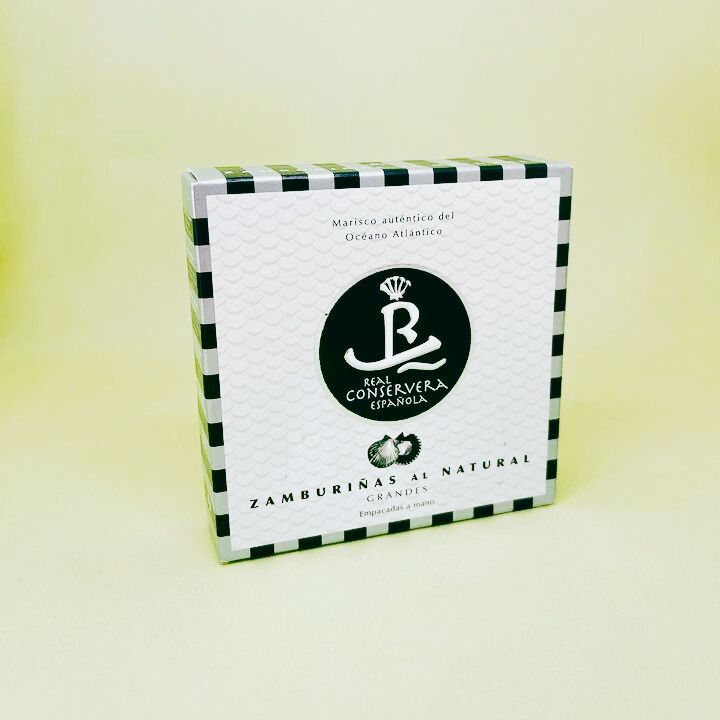

At Güeyu Mar, owner Abel Álvarez has built his reputation on elaborate fire-cooking techniques that introduce subtle smoky elements before preservation. His facility features various traditional cooking structures, including a stone hearth where scallops roast in their shells before preservation and a metal gridiron suspended over embers where squid slowly cooks, developing complex flavor compounds.

"Fire is our oldest cooking technology, yet we still don't fully understand its chemistry," Álvarez explains, adjusting embers with a practiced hand. "There are flavor compounds created through proper fire-cooking that cannot be replicated through other methods."

The mastery of these traditional cooking techniques represents another aspect of conservas production resistant to industrialization. While temperature and time can be standardized, the judgment of when exactly to remove fish from heat relies on sensory expertise developed over years.

"Look at the eyes," instructs a grill master at Conservas Ortiz, pointing to sardines on the grill. "When they turn precisely this shade of white, they're ready—not a moment before or after. No timer can tell you this."

The Maturation Mindset

Perhaps the most distinctive philosophical aspect of traditional conservas production is the concept of maturation—the understanding that tinned seafood isn't static but evolves over time through interactions between fish, oil, and environment.

"We're not just preserving fish as it exists today," explains Carlos Ortiz. "We're creating conditions for it to become something else entirely over months or years in the tin."

This maturation process involves complex chemical interactions as fats from the fish gradually infuse the surrounding oil while compounds from the oil penetrate the flesh. Proteins slowly denature at microscopic levels, creating new textures. Flavors meld and transform through reactions that continue long after the tin leaves the facility.

Understanding and guiding this maturation requires intergenerational knowledge. At Conservas Aréa, production records dating back decades detail how different seasons' fish developed in the tin, creating a reference library that informs current production decisions.

"If September sardines from cool water years develop metallic notes after six months, we adjust the salt levels slightly or modify cooking times," explains the company's master preserver. "These aren't corrections for mistakes but anticipations of how time will transform our work."

This maturation-minded approach creates unusual inventory practices. While modern manufacturing emphasizes just-in-time production and rapid turnover, traditional conservas producers maintain substantial aging rooms where products develop under controlled conditions before release.

At several facilities, I'm shown these sanctum-like spaces where thousands of tins rest on shelves, each batch tagged with production details and periodically sampled to track development. Some producers even rotate tins periodically, much like winemakers might rotate bottles, to ensure even development of contents.

"We're looking for balance between fish character, oil influence, and time effects," notes María at Conservas Brétema, opening tins of the same production from different aging periods. "Some conservas peak quickly—within months. Others need years to show their true character."

This patience-demanding approach explains why fine conservas command premium prices that industrial products cannot match. The inventory carrying costs alone—storing products for months or years before sale—would destroy conventional manufacturing economics.

"We're not selling fish," insists Pedro Martínez. "We're selling time. Each tin contains not just seafood but the accumulated patience of generations."

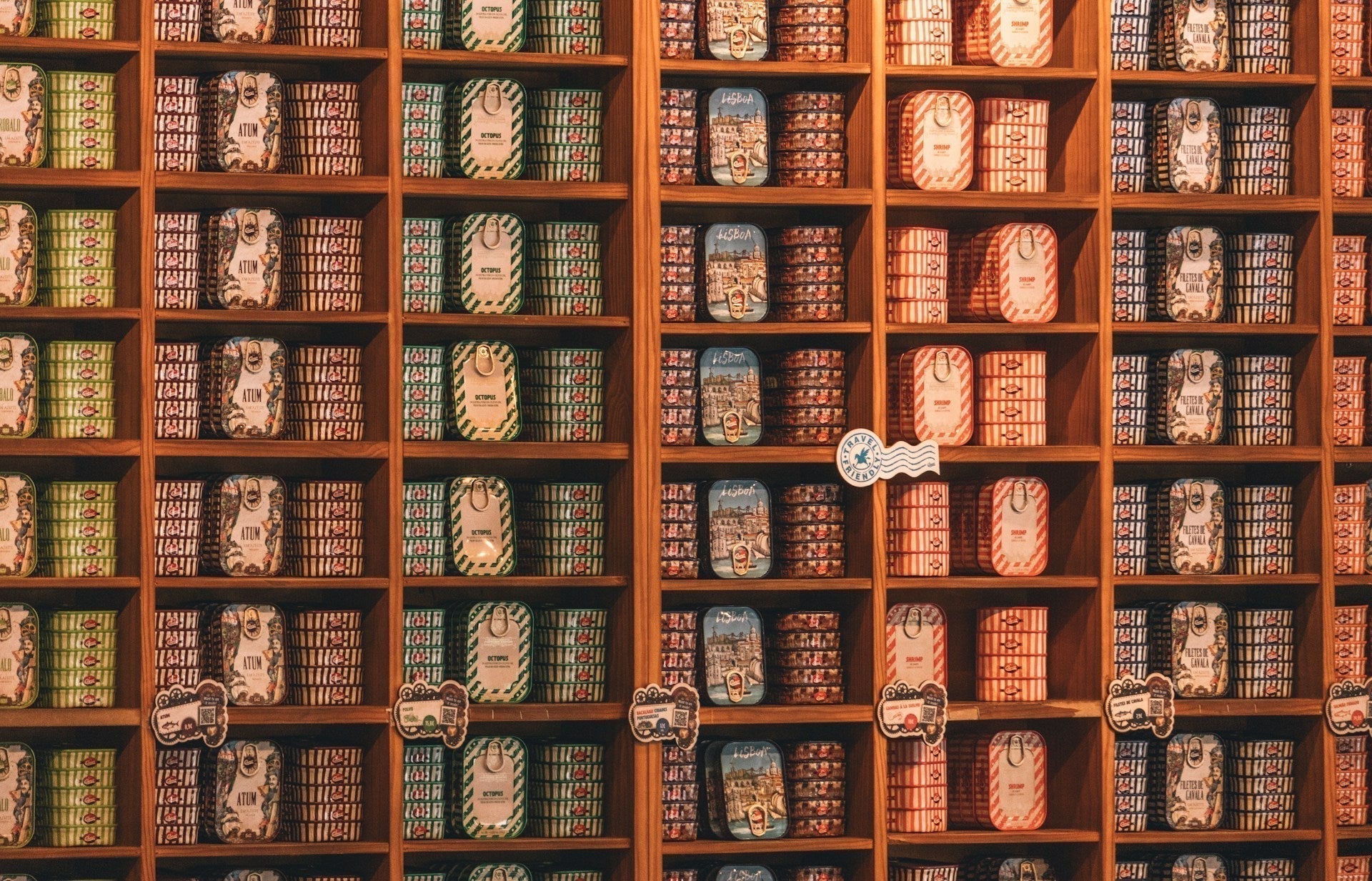

Buy Premium Spanish Tinned Seafood

An Unbroken Lineage

Walking through these facilities, what strikes me most profoundly is the sense of unbroken lineage—practices maintained not through stubborn traditionalism but through recognition of their irreplaceable value.

In Conservas Ortiz's small museum space, I'm shown tools used by the founder in the 1890s that remain remarkably similar to those used today. The company's original copper cooking vessels, while no longer in service, clearly informed the design of their modern counterparts.

"We don't preserve these methods out of sentimentality," Carlos Ortiz emphasizes. "We maintain them because they achieve results that modern shortcuts cannot."

This perspective resonates across producers I visit. While they've incorporated appropriate modern elements—improved sterilization monitoring, better quality control testing, more precise temperature regulation—they've done so while preserving core craft elements that define traditional conservas.

"The question we ask about any potential change isn't whether it's modern or traditional," explains Antonio Pérez. "It's whether it enhances or diminishes the essential character of what we create."

This balanced approach to tradition and innovation has allowed Spain's heritage producers to survive while many artisanal food traditions elsewhere have disappeared under industrialization pressure. By maintaining quality standards that industrial methods cannot match, they've created market positions that protect traditional craftsmanship.

What makes this preservation of technique particularly remarkable is its transmission across generations despite physically demanding conditions and the availability of easier employment alternatives for younger workers.

At Conservas Codesa in Cantabria, I meet 24-year-old Lucía Hernández, who represents the fourth generation of her family working in conservas production. With a university degree in food science, she could have pursued less physically demanding careers but chose to return to hand-processing work.

"I studied modern food technology and came to appreciate even more what we've always done here," she explains, expertly filleting anchovies with the same distinctive knife design her great-grandmother used. "Science is now confirming what tradition discovered through experience—that certain processes cannot be rushed or mechanized without fundamental quality loss."

Heritage in Human Hands

As my exploration of traditional conservas production concludes, I find myself standing on Burela's harbor wall watching fishing boats return as they have for centuries. In an era of relentless technological advancement and industrial scale, the persistence of these hand-crafted methods feels increasingly precious—not as nostalgic curiosity but as living heritage offering lessons about patience, quality, and sustainability.

"What we've maintained isn't just a way of producing food but a way of understanding our relationship to it," reflects Abel Álvarez as we watch his day's carefully selected fish being unloaded. "The hands that clean each fish, the judgment of exactly when to remove it from heat, the patience to let time complete what we've begun—these aren't inefficiencies to eliminate but the very elements that create something meaningful."

In these coastal towns along Spain's Atlantic and Mediterranean shores, traditional conservas production offers an alternative narrative about food creation—one where human discernment cannot be replaced by automation, where seasonal rhythms remain respected rather than conquered, and where time serves as enhancement rather than limitation.

As we face mounting questions about sustainable food systems and meaningful work in automated futures, these traditions offer valuable perspective. The conservas masters have preserved not just seafood but wisdom about our relationship to natural cycles, the irreplaceable value of human touch, and the patience to allow things to develop at their proper pace.

Each tin they produce embodies this philosophy—a small, hand-crafted testament to the proposition that some things simply cannot be rushed or scaled without losing their essential character. In a world increasingly characterized by immediacy and standardization, traditional Spanish conservas remind us of another possibility: that sometimes the old ways endure not because we've failed to find replacements, but because they already achieved perfection that technology cannot improve upon.