The Cultural Transformation of Spanish Conservas and Their 150-Year Legacy

From Necessity to Luxury.

In the coastal town of Burela in Spain's northwestern Galicia region, the morning air carries a briny perfume as fishing boats return to harbor laden with the day's catch. Among them is the Madre del Carmen, a small vessel specializing in bonito del norte—the prized northern albacore tuna that has sustained this community for generations. But the fish unloaded today won't appear on dinner plates tonight. Instead, they'll undergo a transformation that connects past and present—a journey from ocean to tin that represents one of Spain's most enduring culinary traditions.

At Conservas Ortiz, established in 1891 and now in its fifth generation of family ownership, workers stand ready to receive the catch. Within hours, these fish will be meticulously hand-cleaned, filleted, cooked, and preserved in olive oil using techniques virtually unchanged in over a century. The result—elegant tins of bonito that will mature for months before reaching consumers—exemplifies the Spanish conservas tradition that has improbably evolved from practical necessity to global luxury good.

"What my great-great-grandfather created as a way to preserve excess catch and feed local communities has become something else entirely," reflects Carlos Ortiz, the company's current director. "The purpose remains the same—capturing the essence of perfect seafood at its peak—but the meaning has transformed across generations."

This transformation—from utilitarian preservation method to celebrated culinary treasure—offers a compelling lens through which to examine broader shifts in food culture, values, and economies. The story of Spanish conservas reveals how necessity breeds innovation, how cultural practices evolve new meanings across time and borders, and how traditional craftsmanship finds renewed relevance in a modern world often characterized by industrial production and disconnection from food sources.

The Birth of Spanish Conservas: When Necessity Mothers Tradition

Spain's conservas tradition emerged from the intersection of abundance and scarcity that defined coastal life in the 19th century. The rich Atlantic and Mediterranean waters provided bountiful but unpredictable harvests, while inland transportation remained slow and refrigeration nonexistent.

"The fundamental problem facing coastal communities was temporal—how to transform momentary plenty into sustained nourishment," explains food historian Dr. Fernando Gómez. "When fishermen brought in massive spring sardine catches or autumn tuna harvests, the community faced an impossible choice: consume everything immediately or watch valuable protein go to waste."

Early preservation methods included salting, smoking, and drying—techniques dating back to antiquity. But the development of canning technology in the early 19th century revolutionized this dynamic. Nicolas Appert's invention of heat-sealed glass containers and later improvements with tin-plated steel created new possibilities for long-term preservation.

The technology arrived in Spain through multiple channels. French entrepreneurs established early canneries in Galicia around the 1830s and 1840s, attracted by abundant seafood. Returning Spanish naval officers brought canning knowledge from overseas deployments. By the 1850s, local entrepreneurs began establishing distinctly Spanish operations, particularly in Galicia, Asturias, Cantabria, and the Basque Country in the north, and along the southern Mediterranean coast.

"The earliest Spanish canneries were essentially cottage industries," notes industrial archeologist Mariela Sánchez, who studies historical cannery sites. "A family might convert part of their home into a small processing facility, with larger operations eventually expanding into purpose-built factories along harbors."

These early producers faced significant challenges. Tin plate had to be imported from England or France. Quality control was inconsistent, with preservation failures common. Distribution networks were limited, with early conservas primarily serving regional markets.

Despite these obstacles, the industry expanded rapidly in the latter half of the 19th century. The 1880s marked a pivotal period when many of Spain's most enduring conservas brands were established. Conservas Antonio Alonso (now operating as Palacio de Oriente) began in 1873 in O Grove. Conservas Ortiz launched in 1891 in the Basque fishing village of Ondarroa. Ramón Peña started his eponymous company in Galicia in 1920.

"What distinguished these successful early producers was their commitment to quality even in a utilitarian context," explains Gómez. "While they were creating practical food, they insisted on careful selection, proper handling, and appropriate seasoning. This wasn't merely preservation—it was the development of a new culinary category with its own standards and sensibilities."

This foundation established the central paradox that would define Spanish conservas: everyday foods created with extraordinary care. Most early conservas were consumed by working-class families—fishermen, farmers, miners, and factory workers who needed portable, shelf-stable protein. Yet the production methods involved meticulous handwork and artisanal techniques that elevated these products beyond mere sustenance.

From Subsistence to Identity: The Cultural Evolution of Conservas

The first half of the 20th century brought profound challenges to Spain's conservas producers. Two world wars disrupted international trade and metal supplies. The Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) devastated coastal communities and production facilities. The Franco dictatorship's economic isolation policies further complicated export markets.

Yet these difficult decades also solidified conservas' cultural position within Spain. As the country endured hardship, conservas shifted from convenience to necessity—reliable protein during uncertain times. This period cemented emotional and cultural connections to these products that transcended their utilitarian origins.

"My grandfather spoke of how, during the Civil War, a hidden tin of berberechos [cockles] or mussels represented not just food but hope—a connection to normal times and coastal traditions," recalls María Luisa González, whose family has operated a small conservas shop in Madrid since 1925. "These became foods of memory and identity."

The post-war period brought new pressures. Industrialization introduced mechanical processing that threatened traditional methods. Mass tourism beginning in the 1960s created demand for standardized products. International competition, particularly from Portuguese and later Asian producers, forced many smaller Spanish operations to close or consolidate.

Yet a significant cohort of traditional producers persisted, maintaining hand-processing techniques and quality standards even as pressure to modernize intensified. This commitment reflected both practical business considerations—premium pricing justified higher production costs—and deeply held cultural values about proper food production.

"There's a Spanish concept called 'hacer las cosas bien hechas'—doing things properly, with care and attention," explains cultural anthropologist Dr. Elena Martínez. "For many conservas families, maintaining traditional methods wasn't simply nostalgia but a moral position about right relationship to food, community, and heritage."

This cultural positioning proved crucial when Spain's economic and political landscape transformed following Franco's death in 1975. As democracy returned and Spain integrated into the European community, a national conversation emerged about Spanish identity and culture, including culinary heritage.

"The timing was fortuitous," notes food writer Manuel Vázquez. "Just as Spain was rediscovering and redefining its cultural traditions, these conservas producers stood as exemplars of continuous heritage—companies that had maintained quality and tradition through the most difficult periods of Spanish history."

This cultural recontextualization accelerated in the 1990s and early 2000s as the Spanish restaurant scene gained international prominence. Chefs like Ferran Adrià at El Bulli and Juan Mari Arzak began incorporating premium conservas into haute cuisine contexts, elevating their status from home pantry staples to restaurant-worthy ingredients.

"When you saw a tin of Ramón Peña cockles or Don Bocarte anchovies on the menu at a three-Michelin-star restaurant, it forced a reconsideration of the entire category," explains Vázquez. "These weren't compromises or shortcuts but celebrated ingredients with distinct qualities that even the world's best chefs recognized couldn't be improved upon."

This culinary recognition reinforced what many Spanish families had long understood: that conservas represented not merely preserved food but a distinct tradition with its own merits and pleasures. What began as practical preservation had evolved into cultural patrimony—a quintessential expression of Spanish culinary identity.

The Conservas Workshop: Inside Spain's Legacy Producers

Understanding the contemporary cultural significance of Spanish conservas requires examining the distinctive production methods that have remained remarkably consistent across generations despite technological change.

At Conservas Güeyu Mar in Asturias, one of Spain's most celebrated contemporary producers, owner Abel Álvarez maintains a production facility that would be recognizable to canners a century ago. Fish are cooked over wood fires rather than in industrial steamers. Cleaning and packing happen entirely by hand. Each tin is filled with careful attention to aesthetic presentation and precise oil levels.

"We could produce ten times more with automated equipment," Álvarez acknowledges. "But something essential would be lost. The hand-packing allows for judgment—selecting the best cuts, arranging them beautifully, ensuring proper texture. These aren't mechanical decisions."

This commitment to handcraft reflects both practical quality considerations and deeper philosophical positions about proper food production. Spain's legacy producers typically organize their operations around several distinctive principles:

Seasonal attunement: Premium conservas production follows natural cycles rather than constant production schedules. Many facilities operate seasonally, processing specific seafood only during optimal harvest periods. During the "Costera del Bonito" (northern albacore tuna season) in July and August, entire facilities might focus exclusively on this prized catch.

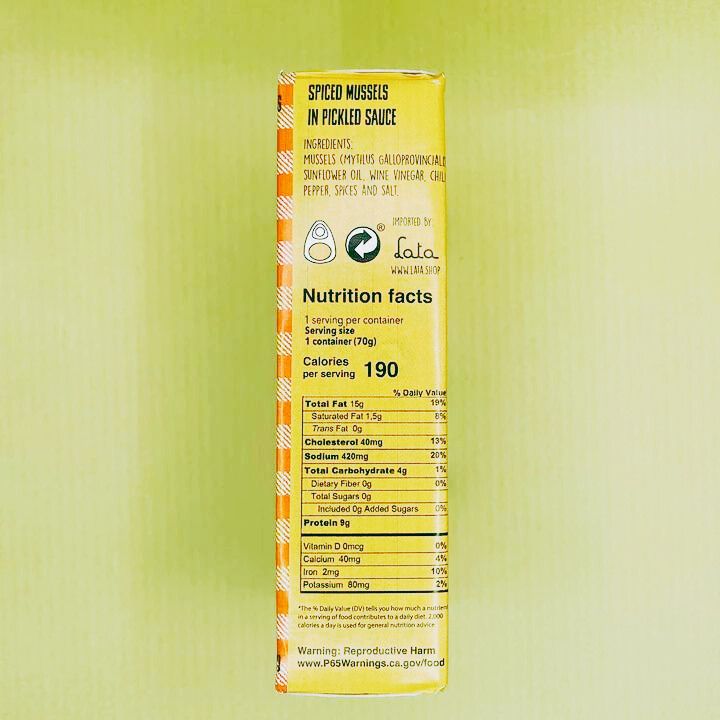

Minimal intervention: The finest producers emphasize minimal processing and additives. "Our ingredient lists typically contain only three components—the seafood, olive oil, and perhaps a touch of salt," explains Antonio Pérez of Conservas Los Peperetes. "When you start with exceptional raw materials and handle them correctly, additional flavoring becomes unnecessary."

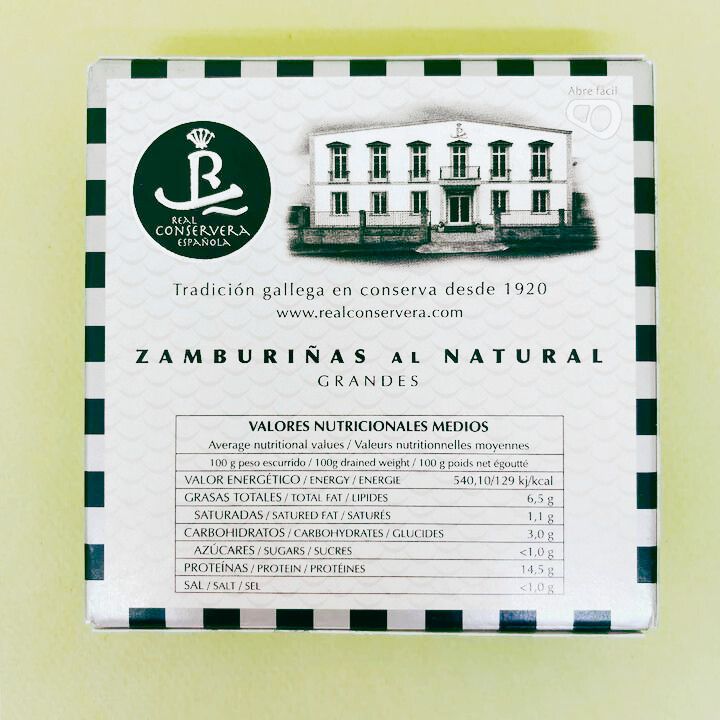

Gender-specific expertise: Traditional conservas production has historically divided labor along gender lines, with roles remaining remarkably stable across generations. Men typically handle initial fish processing and cooking, while women perform the delicate work of cleaning, cutting, and packing.

"The role of redeiras [female packers] represents one of Spain's oldest continuous female professional traditions," notes labor historian Dr. Claudia Fernández. "These women developed specialized knowledge passed from mother to daughter for generations. Their hands are insured like a surgeon's or concert pianist's—they're recognized as bearers of irreplaceable cultural knowledge."

Maturation consciousness: Unlike industrial canned goods designed for immediate consumption, traditional conservas are created with awareness of how products will develop over time. "We're not just preserving the fish as it exists today, but considering what it will become after six months or a year in the tin," explains Carlos Ortiz of Conservas Ortiz.

This maturation process—whereby flavors meld, textures soften, and the interaction between seafood and oil creates new complexities—represents perhaps the most distinctive conceptual aspect of Spanish conservas tradition. It reflects a philosophical orientation toward time that contrasts sharply with contemporary emphasis on immediacy.

Integrated production: Many of Spain's most respected conservas producers maintain direct connections to fishing fleets, ensuring control over raw materials. Conservas Ortiz operates its own boats specialized in line-caught tuna. Güeyu Mar's Abel Álvarez works directly with specific fishermen who understand his quality requirements.

These integrated approaches connect conservas production to broader maritime cultural practices and fishing sustainability. "When you operate your own boats or work directly with fishermen, you're participating in the entire marine ecosystem, not just purchasing commodities," notes sustainable seafood advocate Dr. Macarena López.

The Women Who Preserve: Gender and Heritage in Conservas Tradition

Any examination of Spanish conservas tradition must recognize the central role of women in developing and maintaining these culinary practices. While Spanish fishing remained predominantly male through most of history, conservas production created significant economic opportunities for women in coastal communities.

"The conservas industry effectively created one of Spain's first major female professional workforces," explains labor historian Fernández. "By the early 20th century, thousands of women worked in canneries along Spain's coasts, developing specialized skills that commanded respect and relatively good wages."

These female workers—known variously as empacadoras (packers), fileteadoras (filleters), or simply conserveras—developed remarkable dexterity and speed. A skilled worker could fillet and pack hundreds of sardines hourly while maintaining consistent quality. This work required intimate knowledge of fish anatomy, quality assessment, and aesthetic presentation.

"My grandmother could tell the quality of an anchovy with a single glance," recalls Teresa Rodríguez, third-generation empacadora at Conservas Codesa in Laredo. "She could detect subtle differences in fat content, texture, and size that determined how the fish should be processed and which grade of product it would become."

While early canneries often provided harsh working conditions, the female workforce gradually organized to improve their situation. The Asociación de Conserveras de Bermeo, established in 1920 in the Basque Country, represents one of Spain's earliest female labor organizations. Similar associations formed throughout coastal regions, establishing standards for working conditions and wages.

The gender-specific nature of this work created distinctive cultural patterns in fishing communities. During high seasons when men might be at sea for extended periods, women operated canneries independently. This created unusual economic dynamics where women maintained significant financial control and professional identity.

"These weren't just jobs but careers spanning generations," explains cultural anthropologist Martínez. "In some families, three or four generations of women might work simultaneously in the same facility, with knowledge and techniques passed directly from grandmother to granddaughter."

This generational continuity helped preserve techniques that might otherwise have been lost to industrialization. While large-scale producers increasingly mechanized after World War II, the specialized knowledge of these female workers ensured that traditional methods remained economically viable for premium products.

Today, while mechanization has reduced total employment in the sector, women continue to occupy the most skilled positions in traditional facilities. At Conservas Ramón Peña in Galicia, women comprise over 80% of the production workforce, with many having decades of experience.

"When we say our products are hand-packed, we're really saying they're women-packed," notes Pedro Martínez of Ramón Peña. "These women are the true bearers of our heritage. Without their knowledge and skills, preserved across generations, these traditions would have disappeared long ago."

From Working-Class Fare to Global Luxury: The Remarkable Market Evolution

Perhaps the most striking aspect of conservas' evolution is their market transformation—from affordable staples for workers' lunchboxes to coveted luxury items featured in gourmet shops worldwide. This shift reflects changing notions of value, quality, and authenticity in global food culture.

"What we're witnessing is an inversion of traditional luxury concepts," suggests consumer culture expert Dr. Alicia Wong. "Historically, luxury foods were defined by rarity, exotic origins, or elaborate preparation. Conservas represents something different—everyday items elevated through exceptional quality and cultural authenticity."

This transformation began within Spain during the country's economic development in the 1980s and 1990s. As middle-class incomes rose and food abundance increased, consumers began distinguishing between industrial canned seafood and traditional conservas, creating distinct market tiers.

"The crucial development was that conservas weren't replaced by fresh alternatives as prosperity increased," explains food economist Javier Martín. "Instead, they maintained cultural relevance but shifted categories—from necessity to choice, from everyday consumption to special occasions."

This domestic repositioning laid groundwork for international recognition. As Spanish cuisine gained global prominence in the 1990s and early 2000s, conservas benefited from broader interest in authentic Spanish food traditions. Specialty shops in Paris, London, and eventually New York began featuring premium Spanish conservas alongside wine and cheese.

The market evolved through distinct phases of international adoption:

1990s – 2000s: Culinary Tourism Souvenirs Initial international awareness came largely through tourism. Visitors to Spain encountered conservas in markets and restaurants, purchasing tins as edible souvenirs. This created limited but growing demand in home countries, primarily among culinary enthusiasts who had experienced these products firsthand in Spain.

2000s – 2015: Specialty Ingredient Positioning As international interest in Spanish cuisine expanded, conservas gained recognition as specialty ingredients for home cooking. Food media introduced these products to broader audiences, positioning them as pantry essentials for authentic Spanish dishes like pintxos and tapas.

2015 – Present: Stand-Alone Luxury Status The current phase represents full transformation into stand-alone luxury products, valued for their intrinsic qualities rather than merely as components of Spanish cuisine. This shift coincided with broader consumer interest in artisanal production, food heritage, and sustainable seafood.

"What's remarkable about this evolution is that the products themselves haven't substantially changed," notes food historian Gómez. "Conservas Ortiz produces bonito del norte using essentially the same methods as a century ago. What's changed is cultural context and consumer perception."

This transformation enabled premium pricing that preserved traditional production methods. While industrial canned seafood faces constant pressure to reduce costs, traditional conservas positioned themselves in a market segment where handcraft adds value rather than inefficiency.

"The irony is that economic necessity preserved cultural heritage," suggests economist Martín. "These companies couldn't compete with industrial producers on price, so they doubled down on traditional methods and quality, finding new markets willing to pay for these distinctions."

This market evolution occurred without significant product modification for export markets—unlike many food products that adapt to international palates. Spanish producers maintained traditional recipes and presentations, allowing cultural authenticity to become a selling point rather than a barrier.

"We export to thirty-two countries now, but we haven't changed our products for different markets," explains Carlos Ortiz. "Instead, we focus on education—helping consumers understand why traditional methods matter and how to appreciate these products in their authentic form."

The Old Becoming New: How Ancient Practices Address Contemporary Values

The contemporary appeal of traditional conservas extends beyond flavor and quality to encompass values increasingly prioritized by conscious consumers: sustainability, transparency, tradition, and connection to place.

"What makes the conservas renaissance so interesting is that practices developed decades or centuries ago for practical reasons align remarkably well with emerging food values," notes sustainable seafood advocate López. "Traditional producers weren't trying to be sustainable or transparent—these were simply the natural approaches when operating locally at human scale."

Several aspects of traditional conservas production resonate with contemporary values:

Seasonality and resource management: Traditional producers process specific seafood only during appropriate seasons, working with natural abundance rather than demanding constant supply. This approach stands in contrast to industrial seafood systems that rely on global sourcing to eliminate seasonality.

"My grandfather would close the facility during certain months because the fish weren't at their best," explains Martínez of Ramón Peña. "This wasn't environmentalism—it was common sense. Why process inferior product? Now this seasonal attunement is recognized as both quality-enhancing and environmentally appropriate."

Species diversity: While industrial seafood increasingly concentrates on a handful of internationally marketed species, traditional conservas embrace regional diversity—preserving everything from barnacles (percebes) to small sardine relatives (xoubas) that might otherwise lack commercial markets.

This diversity creates economic incentives to maintain healthy marine ecosystems rather than maximizing single-species harvest. Fishermen supplying traditional canneries typically use selective methods—hand lines, small nets, or traps—that minimize bycatch and habitat damage.

Waste reduction: Well before "nose-to-tail" eating became fashionable, conservas production utilized various parts of each fish for different products. Prime fillets might become premium conservas, while other portions are processed into pâtés or lower-priced products.

"Nothing is wasted in traditional production," notes Álvarez of Güeyu Mar. "Even the bones and heads typically become stock for other preparations. This wasn't environmental consciousness—it was economic necessity and respect for the resource."

Transparent supply chains: Many legacy producers maintain direct relationships with specific fishing boats and crews, creating traceability that has become increasingly valued by conscious consumers. Some premium tins even identify the specific boat that caught the fish or the name of the person who packed it.

Cultural preservation: Beyond environmental considerations, conservas production preserves cultural knowledge, traditional skills, and regional identity that might otherwise disappear in an increasingly homogenized food system.

"When you purchase traditional conservas, you're not just buying seafood—you're supporting the continuation of knowledge that might otherwise be lost," explains cultural anthropologist Martínez. "These products represent living heritage, maintaining techniques and sensibilities developed across generations."

This alignment between historical practices and contemporary values helps explain why traditional conservas have found receptive audiences among younger consumers often characterized by interest in food ethics, production transparency, and cultural authenticity.

"It's powerful to discover that your great-grandparents' generation already solved problems we're struggling with today," suggests Wong. "Traditional conservas demonstrate that care, quality, and sustainability needn't be modern innovations—sometimes they're traditional wisdom we've temporarily forgotten."

Preserving the Future: Challenges Facing Spanish Conservas Tradition

Despite renewed appreciation, Spain's traditional conservas heritage faces significant challenges that threaten its long-term viability. Industry stakeholders navigate tensions between commercial success and cultural preservation, modernization and tradition, global opportunity and local identity.

"The greatest risk isn't lack of demand—premium conservas have never had broader markets," notes industry analyst Xavier González. "The challenge is maintaining the distinctive qualities that created this demand while adapting to contemporary business realities."

Several crucial issues confront the sector:

Succession challenges: Many traditional producers are family businesses now in third, fourth, or fifth generations. As younger family members pursue other careers, these companies face difficult transitions. Some have sold to larger food conglomerates, raising questions about commitment to traditional methods under new ownership.

"Our greatest worry isn't competition but continuity," acknowledges Martínez of Ramón Peña. "Making conservas traditionally is demanding work with tight margins. Convincing the next generation to continue requires more than financial incentives—it requires cultural commitment."

Knowledge transfer: The specialized skills of master packers, many nearing retirement age, represent irreplaceable cultural heritage that can only be transmitted through extended apprenticeship. As younger workers seek less physically demanding employment, this knowledge transfer becomes precarious.

Climate change impacts: Rising ocean temperatures and changing marine ecosystems affect fish migration patterns, abundance, and quality. Species that have been conservas mainstays for generations may become scarcer or shift habitats, threatening traditional production patterns.

Authentication and standards: As demand for premium conservas grows, questions about authentication and quality standards become increasingly important. Unlike wine or cheese, conservas lack formal appellation systems or protected status designations to help consumers distinguish traditional products from industrial imitations marketed with artisanal aesthetics.

"The term 'conservas' itself has no legal protection," explains González. "Any producer can use traditional-looking packaging and artisanal language regardless of actual production methods. This creates market confusion that potentially undermines authentic producers."

Scale limitations: Traditional methods inherently restrict production volume, creating tension between market growth and quality maintenance. Some producers have expanded by building multiple small-scale facilities rather than industrializing existing operations, but this approach requires significant capital investment.

Price sustainability: Premium positioning has preserved traditional methods by supporting higher production costs, but this position remains vulnerable to economic downturns or changing consumer preferences. If premium conservas become seen as mere luxury indulgence rather than cultural heritage, their market could prove more volatile.

Despite these challenges, many legacy producers remain cautiously optimistic, believing that authentic quality creates its own security in an increasingly standardized food landscape.

"My great-grandfather survived the Spanish Civil War. My grandfather navigated postwar scarcity. My father adapted to European market integration," reflects Carlos Ortiz. "Each generation faced existential challenges, yet our commitment to quality preserved us. I believe this remains our best security for the future."

This perspective reflects a distinctive Spanish concept—duende, an ineffable quality of authenticity and soulfulness that transcends mere technical excellence. Many producers believe that traditional conservas possess this quality, creating value that industrial production cannot replicate regardless of technological advancement.

"In the end, what we're preserving isn't just fish," suggests Álvarez of Güeyu Mar. "It's a way of understanding food as connection—to place, to tradition, to the hands that transformed it. This understanding becomes increasingly precious in a world where such connections grow rarer."

Beyond the Tin: The Broader Cultural Significance

As Spanish conservas reach their 150th anniversary as formalized commercial products, their cultural journey offers broader insights about food's changing meanings across time and borders. Few food categories have undergone such dramatic recontextualization while maintaining essential production methods—a transformation that illuminates changing relationships between necessity and luxury, tradition and innovation, local and global.

"The conservas story demonstrates something profound about how food acquires meaning," suggests food philosopher Dr. Carlos Menéndez. "These products began as solutions to material problems—preserving abundant seafood without refrigeration. Yet over generations, they accumulated layers of cultural significance that transcended their utilitarian origins."

This evolution challenges conventional narratives about food and social class. Unlike many traditional foods that originated in wealthy kitchens before democratizing (like champagne or chocolate), conservas followed the opposite trajectory—working-class staples that became luxury items while remaining essentially unchanged.

"This inversion tells us something important about contemporary food values," argues Menéndez. "We increasingly recognize that foods developed through practical wisdom often possess qualities that industrialization eliminated in the name of efficiency or consistency. What was once considered ordinary—hand-processing, seasonal production, intimate producer-consumer relationships—has become extraordinary."

The conservas journey also illuminates how food traditions migrate across cultural contexts, acquiring new meanings while maintaining connections to origin. Rather than adapting products to match American preferences, Spanish producers successfully maintained authentic traditions while helping new consumers develop appreciation for unfamiliar flavors and presentations.

"This represents cultural exchange at its best," suggests anthropologist Martínez. "Rather than diluting tradition to increase accessibility, conservas producers invited consumers into their cultural context. The result enriches both parties—producers maintain authentic practices while gaining new markets, while consumers discover flavors and approaches they might never have encountered otherwise."

Perhaps most significantly, the conservas renaissance demonstrates how traditional food practices can find renewed relevance by addressing contemporary concerns about environmental sustainability, production transparency, and meaningful connection to food sources.

"What makes traditional conservas so powerful isn't nostalgia but relevance," argues sustainable food advocate López. "These century-old practices speak directly to our most pressing contemporary food challenges—how to consume seafood responsibly, how to value quality over quantity, how to maintain cultural diversity in an increasingly homogenized food system."

As Elena García, a 78-year-old retired empacadora who spent five decades packing anchovies in Santoña, watches her granddaughter continue the family tradition, she reflects on this enduring relevance.

"When I began this work as a girl, we weren't trying to create something special—we were simply making food the proper way with the knowledge passed to us," she explains, her hands still moving automatically through the motions of cleaning tiny fish. "That this work now receives recognition feels like a validation. The world has changed enormously, but good food made with care and respect remains important. Some truths are constant across time."

In this observation lies perhaps the most profound lesson of Spanish conservas' remarkable journey—that practices developed by ordinary people facing practical challenges can, over time, reveal themselves as extraordinary cultural treasures, connecting generations across centuries through the simple yet profound act of preserving the bounty of the sea.

SIDEBAR: TIMELINE OF SPANISH CONSERVAS

1810: Nicolas Appert publishes first comprehensive guide to canning in France

1840s: First commercial canneries established in Galicia by French entrepreneurs

1861: First fully Spanish-owned cannery founded in O Grove, Galicia

1873: Antonio Alonso establishes La Casa Alonso (now Palacio de Oriente)

1879: First Spanish cannery workers' association formed in Vigo

1891: Conservas Ortiz founded in Ondarroa, Basque Country

1908: First Spanish regulation of canned food production enacted

1920: Ramón Peña establishes his eponymous company in Galicia Women canners form first labor association in Bermeo

1936-1939: Spanish Civil War disrupts production; many facilities damaged

1950s: Post-war modernization introduces first mechanized processes

1970s: Spain transitions to democracy; conservas export markets expand

1990s: Traditional conservas gain recognition in Spanish haute cuisine

2000s: Premium conservas achieve international market recognition

2010s: Social media drives global interest; American market growth accelerates

2020s: New generation of Spanish producers combines tradition with innovation

SIDEBAR: REGIONAL CONSERVAS SPECIALTIES

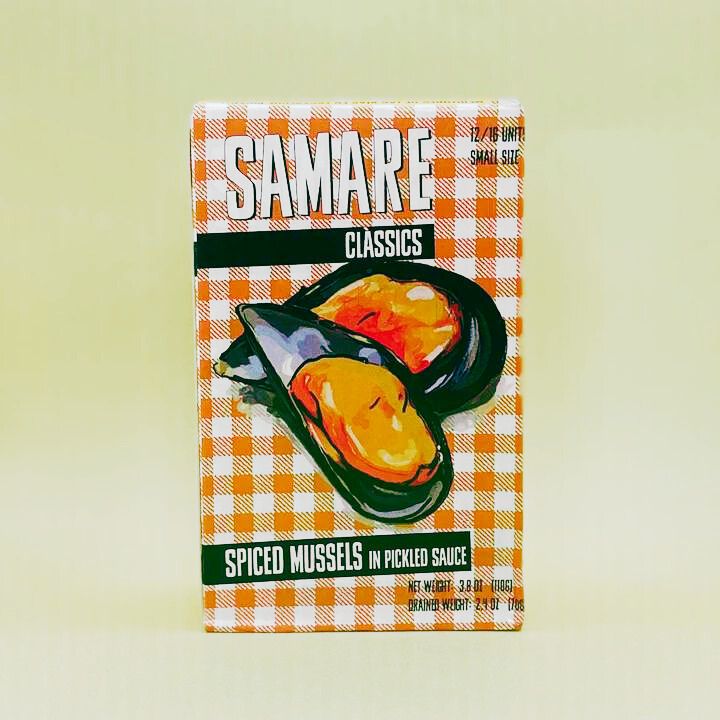

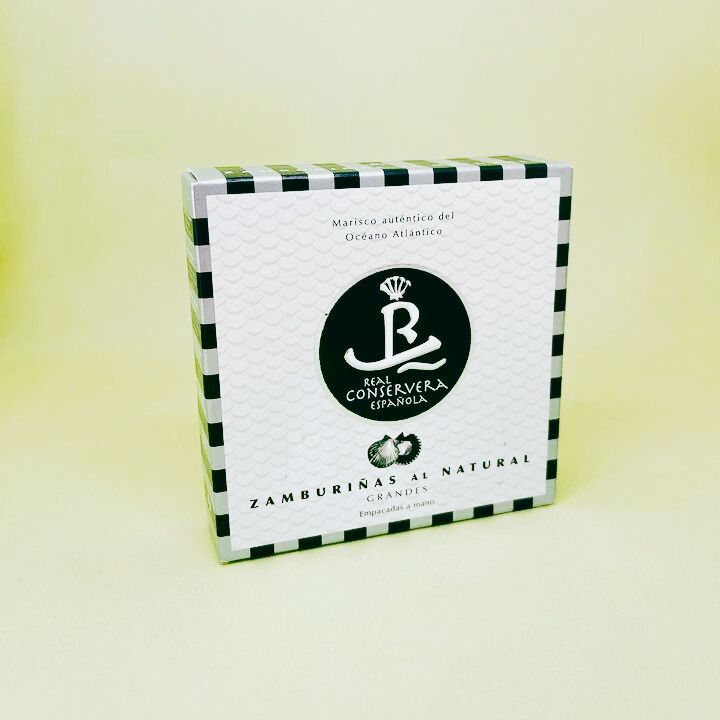

Galicia: The epicenter of Spanish conservas production, known for mussels (mejillones), small scallops (zamburiñas), octopus (pulpo), and sardines. Galician producers typically use lighter olive oils and minimal seasonings to highlight seafood's natural flavors.

Cantabria: Famous for anchovies (anchoas), particularly from the town of Santoña, where unique curing methods create distinctive nutty flavor profiles. Also known for tuna and bonito preserved in regional olive oils.

Asturias: Known for traditional wood-fired cooking techniques that create smoky notes in preserved seafood. Specialties include smoked sardines, mackerel, and innovative approaches like chargrilled squid in ink sauce.

Basque Country: Famed for line-caught bonito del norte (white tuna) and traditional preparation methods that emphasize texture. Basque conservas often feature richer olive oils and distinctive piquillo peppers as accompaniments.

Catalonia: Specializes in Mediterranean species like anchovies from L'Escala and sea urchin. Catalan conservas often incorporate regional aromatics like nyora peppers and saffron.

Andalusia: Known for preserved bluefin tuna (atún rojo) using traditional almadraba fishing methods dating to Phoenician times. Also produces distinctive conservas featuring local shrimp and mojama (salt-cured tuna).